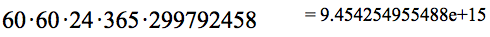

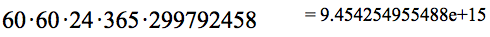

Figure 1.1.1. GC's display of calculating $60\cdot 60\cdot 24\cdot 365\cdot 299792458$

| < Previous Section | Home | Next Section > |

We will investigate quantities in our everyday experience so large or so small they are hard to envision. Then we will see how the ideas of large and small are intimately related.

You will need to change units of measure in many of this chapter’s exercises. This is because units of measure are often presented in an appropriate magnitude to state measures in small numbers of them.

However, scientists often have to relate two quantities expressed in different units, so they must change from one unit to another. Dealing with large and small quantities also often requires we use scientific notation.

Astronomical distances are measured in light-years, or the distance light travels in one year. But a light-year is expressed in terms of meters.

To calculate the distance light can travel in one year in meters, we need to know the speed at which light travels, in meters per second, and the number of seconds in a year.

The speed of light in a vacuum is exactly $299\,792\,458$ meters/sec. We can say this number is exact because in 1983 the meter was defined as $\dfrac{1}{299\,792\,458}$ the distance light travels in one second.

The second as a unit of time is defined as the duration of $9\,192\,631\,770$ cycles between two energy levels of the cesium 133 atom.

The number of seconds in a year as we normally think of a year is less exact, because one year (the time for earth to revolve once around the sun) differs slightly from one revolution to the next.

For our purposes, we will take one year to be 365 days, one day to be 24 hours, one hour to be 60 minutes, and one minute to be 60 seconds.

Therefore, the distance light travels in one year is

$$\mathrm{60 \frac{sec}{min} \cdot 60 \frac{min}{hr} \cdot 24 \frac{hr}{day} \cdot 365 \frac{days}{yr} \cdot 299792458 \frac{meters}{sec}}$$

Type this product into GC, without the units, using "*" for multiplication.

You will see something resembling Figure 1.1.1. The part "e+15" means "$\times 10^{15}$". GC displayed its result to 13 significant digits. Your number of significant digits is determined by GC's setting in the File/Document Properties menu.

The exact value of this product is $9\,454\,254\,955\,488\,000$ meters, or about 9.5 million billion meters. A particle of light travels a lot of meters in one year.

How many trips to the moon and back is one light-year? The average distance from earth to moon is 384 400 km, or $384\,400\,000$ meters. Use GC to calculate the number of round trips to the moon equivalent to $9\,454\,254\,955\,488\,000$ meters (one light-year).

One light-year is more than 12 million round trips to the moon. Put another way, a pulse of light would make 12 round trips to the moon in less than one-millionth year.

A pulse of light would make how many round trips to the moon in one second?

But one light-year is also a small distance. One light-year is about $\dfrac{4}{17}$ the distance to Proxima Centauri, the nearest star to Earth outside our solar system. At the same time, a light-year is approximately $\dfrac{1}{106\,000}$ the width of the Milky Way and is approximately $\dfrac{1}{45\,000\,000\,000}$ (one forty-five-billionth) the distance from earth to the edge of the visible universe. The point is, large quantities are large compared to smaller quantities, but they can be very small compared to much larger quantities.

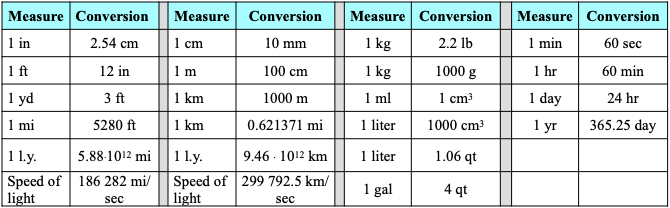

The International System of units (SI) is standard around the world, including the United States. The U.S. also uses a common system of units based on the old English system. Here are some facts about units you can use in the following exercises.

Common Abbreviations

Common Conversions

Large Units

Speed of light = $299\,792\,458$ meters per second

Average distance from Earth to Sun = $149\,597\,870.7$ km

Distance from earth to edge of visible universe = $4.6 \cdot 10^{10}$ light-years

Use GC for your computations. Enter "*" for multiplication, "/" for division, shift-6 ("^") for an exponent, "$\downarrow$" to exit an exponent, "$\rightarrow$" to move to the next term.

You might be tempted to use your personal calculator for these exercises. PLEASE DON'T DO THIS. Use GC. It is by using GC that you will become comfortable using it. Being comfortable with GC will be very important for later chapters.

The probability of two or more independent events all happening is the product of their individual probabilities. Compare the probability of Joan winning all four lotteries with the probability of picking, at random, a grain of sand painted red hidden somewhere within the Sahara desert.

| < Previous Section | Home | Next Section > |